This is an operation that is invariably performed on almost all projects, and the way of doing it is so simple that we usually end writing a function for it every time. But ARM microcontrollers have a better way: they have a specific instruction for it!

The CPU instruction

The instruction used for this is REV, and have the following syntax:

REV {cond} Rd, Rn

where:

- ‘

cond’ is an optional condition code, to have conditional execution - ‘

Rd’ is the destination register - ‘

Rn’ is the register holding the operand, that is: the original data.

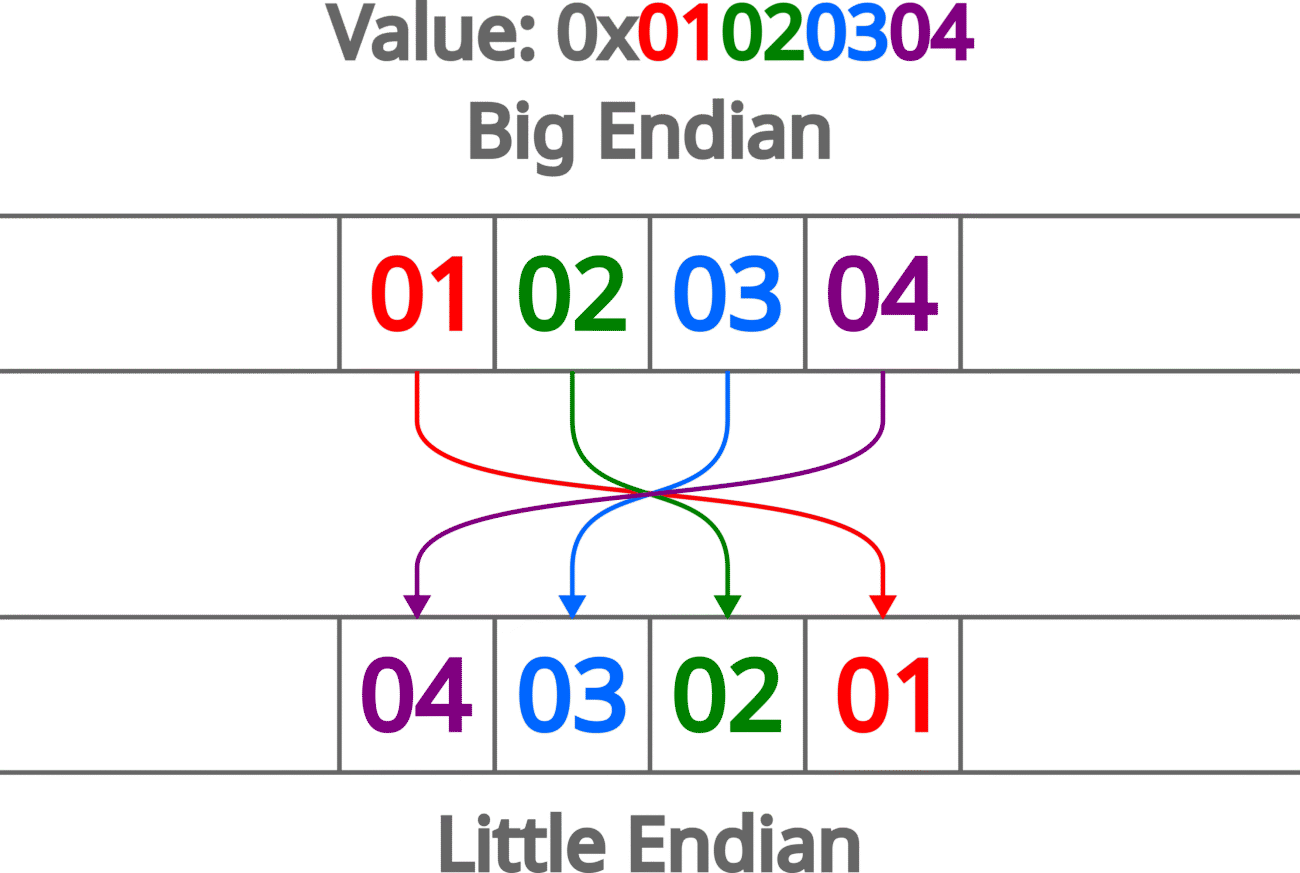

This instruction converts a 32 bit big-endian data to little-endian data or the other way around. It basically just swaps the bytes.

I know what you are thinking: “I don’t want to use assembly code”. And you are right! Using assembly code is always playing with fire.

Luckily, we have an intrinsic functions that help us with this:

The intrinsic function

CMSIS defines a __REV() function that we can use for this purpose. The exact implementation may wary, and it can be converted to the actual rev assembly instruction either by the compiler or by a define, depending on, among other thing, the compiler and the compiler version that you are using.

Intrinsic functions works in the usual way: you pass one or more argument to it, and they return a value. If you are using GCC, __REV() is declared and defined in cmsis_gcc.h with the following signature.

__STATIC_FORCEINLINE uint32_t __REV(uint32_t value)

To use it, you just have to call it with the value that you want to reverse, and get the return value

littleEndianVar = __REV(bigEndianVar);

That’s it.

It will get your value and put the swapped bytes in the destination variable.

Note: CMSIS privides __REV() as a standardized name. When using the GCC compiler the function is typically a wrapper that calls GCC’s own internal function for this task: __builtin_bswap32().

A little test

To verify if it really gives an advantage, and check what it is, I’ve wrote a little program to actually measure the time it takes to compute the operation. I’ve run it on a STM32F103RB, and I use a GPIO to measure the time.

Here is the code:

volatile uint32_t bigEndianVar;

volatile uint32_t littleEndianVar, littleEndianVar2;

shouldRun = 0;

bigEndianVar = 0x01020304;

//as reference

LL_GPIO_SetOutputPin(DBG_OUT_GPIO_Port, DBG_OUT_Pin);

LL_GPIO_ResetOutputPin(DBG_OUT_GPIO_Port, DBG_OUT_Pin);

LL_GPIO_SetOutputPin(DBG_OUT_GPIO_Port, DBG_OUT_Pin);

littleEndianVar = __REV(bigEndianVar);

LL_GPIO_ResetOutputPin(DBG_OUT_GPIO_Port, DBG_OUT_Pin);

LL_GPIO_SetOutputPin(DBG_OUT_GPIO_Port, DBG_OUT_Pin);

littleEndianVar2 = ((bigEndianVar >> 24) & 0x000000FF) |

((bigEndianVar >> 8) & 0x0000FF00) |

((bigEndianVar << 8) & 0x00FF0000) |

((bigEndianVar << 24) & 0xFF000000);

LL_GPIO_ResetOutputPin(DBG_OUT_GPIO_Port, DBG_OUT_Pin);

printf("bigEndianVar : %08lX\n", bigEndianVar);

printf("lilEndianVar : %08lX\n", littleEndianVar);

printf("lilEndianVar2: %08lX\n\n\n", littleEndianVar2);The variables are declared volatile, because I’ve run the code also with optimizations and without it would have been optimized away.

I use the Low Level library for the setting and clearing the GPIO line that I use for timing, as it have a smaller overhead.

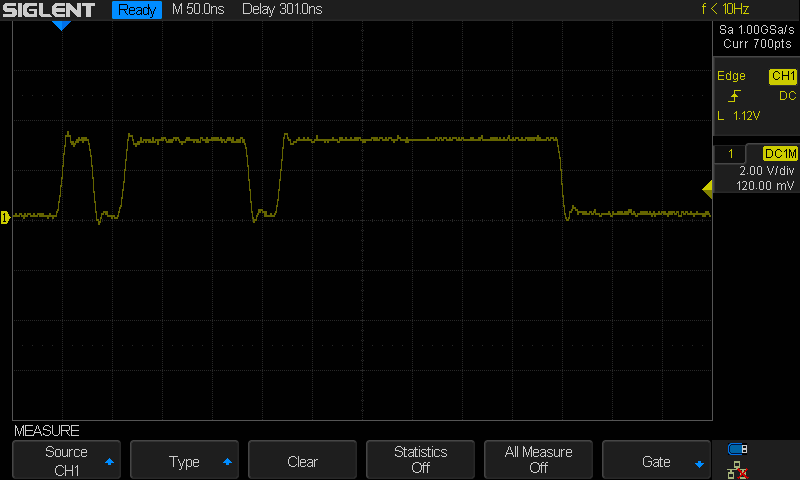

The first pulse is used as a reference, to know how much time it takes to set and clear the GPIO. Its duration has to be removed from the length of the other two.

The second pulse is using the intrinsic function __REV(), and the third one measure the time of the usual way of reversing endianness.

Here is the oscilloscope trace:

The MCU runs with a clock at 64 MHz, so we can actually calculate how many cycles are required for each operation, as we know that each clock cycle last 15.625 ns.

| What | Length [ns] | Operation length [ns] | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference pulse | 31 | 31 | 2 |

__REV() | 124 | 93 | 6 |

| Shifting and masking | 281 | 250 | 16 |

This shows that the intrinsic function is much faster. ~2.6 times faster than the shift and mask operation.

Most of the times that’s negligible, but there are cases when it may make a difference:

- you are doing this operation very often

- you need to do it within an interrupt service routine

- you are using a slow clock

- you need to reduce the memory footprint

In any case, using the intrinsic function is so simple that it may not even be worth thinking about it.

Since this instruction is part of all ARM Cortex M architectures, you’ll always have a gain.

Speaking of memory footprint, let’s look at the assembly.

0800032b: str r2, [r4, #16] @setting the GPIO

0800032d: str r2, [r4, #20] @clearing the GPIO

0800032f: str r2, [r4, #16] @setting the GPIO

08000331: ldr r3, [sp, #0] @loading the value to reverse

08000333: rev r3, r3 @reverse the value

08000335: str r3, [sp, #4] @store the reversed value

08000337: str r2, [r4, #20] @clearing the GPIO

08000339: str r2, [r4, #16] @setting the GPIO

0800033b: ldr r6, [sp, #0]

0800033d: ldr r0, [sp, #0]

0800033f: ldr r1, [sp, #0]

08000341: ldr r3, [sp, #0]

08000343: lsrs r0, r0, #8

08000345: lsls r3, r3, #24

08000347: orr.w r3, r3, r6, lsr #24

0800034b: and.w r0, r0, #65280 @ 0xff00

0800034f: lsls r1, r1, #8

08000351: orrs r3, r0

08000353: and.w r1, r1, #16711680 @ 0xff0000

08000357: orrs r3, r1

08000359: str r3, [sp, #12]

0800035b: str r2, [r4, #20] @clearing the GPIO

There are a couple of things worth noticing:

- The GPIO operations are where we’d expect them to be. That’s good as it means that we’re actually making a correct measurement. Optimizing the code may alter the order of operations, but let’s save this for another time.

- Using the intrinsic function uses much less operations. The gain here is even more clear.

If we look at the amount of instructions stored we see

| What | Start address | End address | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

__REV() | 0x08000333 | 0x08000337 | 4 |

| Shifting and masking | 0x0800033b | 0x0800035b | 32 |

Here we see that with the intrinsic function we use 1/8 of the shift and mask solution.

Of course, if you use a function to reverse, instead of inlining as in the example, you are only going to pay the price once, but a function call is also expensive both in term of memory and time.

Conclusions

While the usual way of reversing endianness is both portable and clear, the data speaks for itself. On an ARM Cortex M MCU, using the _REV() intrinsic function provides a measurable advantage in both performance and code size: 2.6x execution speed, and 8x reduction in memory footprint. Leveraging this specific hardware feature with the simple intrinsic should be the default choice in any embedded application where performance is a must.